II. THE BIBLICAL REFERENCE DOCUMENTS USED BY BIBLINDEX2

To enlarge its corpus as quickly as possible, Biblia Patristica used a single biblical reference framework, a composite Bible made up of the following:

• the books of the Hebrew Bible as given in modern editions of the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament;

• the books of the Septuagint in Rahlfs’ edition for seven other texts that do not belong to the Hebrew corpus: 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus (Sirach), Tobit, Judith, Baruch (1-6)3 and the Greek additions to Esther and Daniel.

The Vulgate and the Vetus Latina were not taken into account. The verse numbering of the Jerusalem Bible was always used.

A. Multilingualism

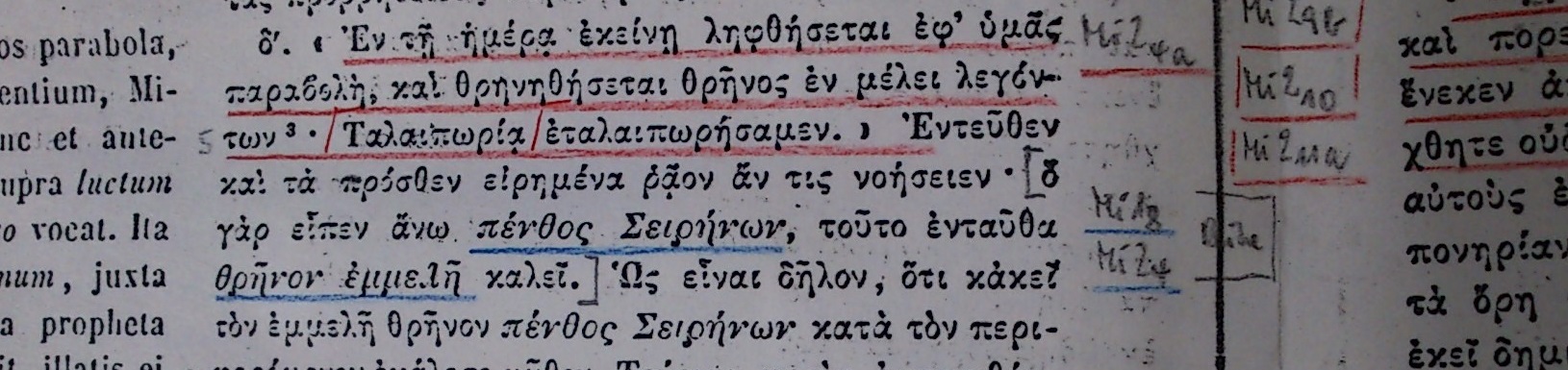

The terms of reference were thus defined not from the objects to be dealt with but from the modern researcher’s constraints: while the canon accepted by the Fathers was varied and fluid, the division of the Hebrew Bible results from a consensus of modern scholars. It was more practical to use a single, albeit inadequate, scheme. Nonetheless, quotations in different languages have to refer to different ‘Bibles’. Even in the same author’s work, references to multiple sources may be found, as in the case of Jerome with his use of Hebrew, Greek and various Latin texts.

BiblIndex, like Biblia Patristica, requires biblical systems of reference so that analysts can give easily identifiable chapter and verse numbers to modern Bible readers. However, a reference edition is normally a form of text unknown to Fathers who quoted the Bible. Yet, the same problem arises as for the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae when it uses texts re-constructed in the editing process of the Vetus Latina: a reference edition built in this way remains a form of the text unknown to the Fathers who cited the Bible. These referentials are in no way prescriptive and have no more real existence for the Fathers than the Jerusalem Bible, even if they are a better approximation. There is, of course, no question of our ‘referring’ Cyprian’s text to the Vulgate. Rather, when reading the biblical text of Cyprian, we may note what sets it apart from the Vulgate. In the absence of the biblical text which was actually used by the Fathers, the only function of the biblical reference documents is provisionally to relate any patristic text to a shared point of comparison.

Insofar as the text of the patristic quotations will be gradually integrated into the database, we can eventually reconstruct the Bible of a particular author and, if necessary, set new referentials, depending on the research interest. One could, for example, compare the Bibles of two authors, or one author’s Bible at different periods of his life, or several authors’ Bibles in a specific geographic area over a given period, and so on. However, this ideal phase will only be completed when a very consistent number of texts have been analysed and integrated into the corpus of BiblIndex. It must be added that the use of biblical referentials allows, in this first phase of the project, the integration of both texts analysed anew and reference lists reconstructed from biblical apparatus or the available archives. This is a sine qua non for a significant increase of the corpus.

Initially in Biblindex, in addition to translations into modern languages – the new TOB in French, the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) with the so-called deuterocanonical books/Apocrypha in English – which will be seen only in the user interface, five biblical reference documents are proposed:

- the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartiensia;

-

Rahlfs’ Septuagint and the Greek New Testament (NA 27);

- the Weber–Gryson Vulgate for the Latin texts;

- the Peshitta and the Syriac New Testament;

- the Zohrab Bible (Venice, 1805, recently reprinted) for texts written directly in Armenian. For Armenian versions of Greek and Syriac texts, the Bible of the original source (i.e. Septuagint or Peshitta) is taken as the reference.

(see "Text credits")